I first met Richard Pflum in Bloomington in the late 1970s. He was one of a group of hard-working and established poets, all of whom I greatly admired—writers who helped homestead a fertile poetry ground in Indianapolis and Bloomington, a group which included Alice Friman, Tom Hastings, Roger Pfingston, Jim Powell, and others. As a relatively young poet, I was struck by the generosity of these writers and their willingness to include my contemporaries and me in their arena.

Dick Pflum was then, and has remained, a gentle soul of the purest sort. His lovely collection, A Dream of Salt, was a book I turned to for instruction and inspiration. I was immediately struck by Dick’s “angels,” otherworldly voices that entered his poems as if something larger than an individual ego was stepping up from tree roots and down from chords of light to say something important and valuable. Humor played a role in Dick’s poems, at times a self-deprecating appreciation of one’s own fallibility.

The recent work of his I’ve gathered here strikes me as a continuation of a vision to which he’s remained steadfast and devoted. Dick’s poems can be difficult to “locate” as belonging to this school or that—and that is one of their many charms. I love the vulnerable yet steady voice in his poems that often reminds me of the crazy mess of being human.

After some thirty years of falling out of touch with Dick’s work, I am happy to have fallen back onto its path. I hope you enjoy this feature, which includes a group of his poems and an interview. It indicates, I believe, just some of the richness of contemporary Indiana poetry and sets the table for additional features of other fine Indiana poets in this forum. The Wabash Watershed is fortunate to have this work. I am grateful for the poetry of Richard Pflum.

—George Kalamaras

Biographical Note

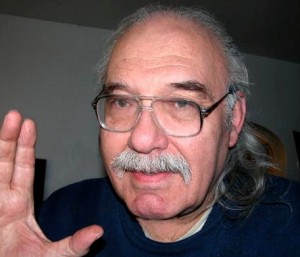

Richard Pflum was born July 2, 1932 in Indianapolis. He graduated from Purdue University in 1956 with a B.S. in Chemistry and with many electives in English. He has published three collections of poetry, A Dream of Salt (The Raintree Press, 1980), A Strange Juxtaposition of Parts (Writers’ Center Press of Indianapolis, 1995), and Some Poems to be Read Out Loud, (Chatter House Press, 1995). His poems have appeared in such anthologies and venues as Art & Poems (Exhibition catalog from Arts Kaleidoscope, Muncie, Indiana), Bear Crossings, Chopin with Cherries, Glassworks, and The New Geography of Poets, as well as in many magazines, including Conceit Magazine, Event, Kayak, Sparrow, and the Tipton Poetry Journal. His more recent selections are in two chapbooks: The Haunted Refrigerator and Other Poems (Pudding House Publications, 2007) and Listening with Others (The Muse Rules Press, 2007). He was a Fellow at the MacDowell Colony in the mid 1970s, and he was nominated for a Pushcart Prize both in the spring of 2008 and in the fall of 2010 for poems published in the Tipton Poetry Journal. In 2010, he was co-winner of the Moving Forward – Cultural Trail Prize (where a poem was chosen to be placed on public display in a bus stop shelter along a path of aesthetic interest through central Indianapolis). He hosts a poetry reading series, An Evening with the Muse, for the Indiana Writers’ Center, in Indianapolis.

Poems

Summer is the Month Everyone Goes Away:

up into the mountains and faraway hills, into the forests,

the long, grassy plains, milky beaches, the air-conditioned

vistas. All go marching-off . . . troops with a taste for the sea,

cool lakes, rivers, those sweet, violet-tinctured sunsets.

All are in lock step but break cadence crossing bridges

as each must find the safe path back. Back to jobs, back

to where they had learned to walk, learned to live with

weather sometimes blue, sometimes grayly ominous.

Back to where parents once draped gauzy veils over cribs as

protection against sun, the flies, the pestilent mosquitoes; shaded

little ones from torpor, the closeness of hot, hazy mornings.

Here, where death and life finally become congruent,

disclose a soluble border, where, without some relief, one

could have easily melted through . . . had weather gone

__________________________________exceedingly wrong.

Autopsy

An isthmus bridging to some lost colony of

homunculi, a frayed umbilicus under a microscope,

metaphysically and perhaps even spiritually

connecting to the surrounding blear-eyed Angels

with their scalpels and saws. One holds up

the heart, and there it is, several pounds of

blue-red meat. Another probes into the glistening

open bowl to touch the cheesy pink and gray

mass of the brain. “Where is it?” someone asks,

digging into the liver while yet another presses

two wires of a battery into fibrous tissue to enliven

a flayed calf muscle in the left leg. An apprentice

philosophizes on the shrunken generational

member so strangely at rest along the upper thigh,

that maybe it is the third leg of some smashed

tripod which fitted the sad camera between

the cold thighs of the woman under the faded

green sheet in the next room.

And so it proceeds, each part removed, taken

apart, weighed, described onto tape, or sketched

by a latexed hand onto a white linen pad.

But they can’t find it anywhere. Something

essential is missing, a something not there even

if everything were broken apart into its final

molecule or atom. “So much hardware here

but never its complementary software,” complains

the noble Archangel impatiently. “Not even a

useful menu,” says a Cherub-apprentice smacking

his lips, hoping for a lunch break soon, hoping

someone will finally recover a relevant

detail, and the file will be found into which

this whole stinking mess might fit.

Joining the Community of Ghosts

We are friends now and I’m told that I might eventually

be elected to their Board of Trustees if I continue

to work for their interests. What I’d like is that I not

be required to wear a suit and tie at the meetings, that

even a bit of bone or decaying flesh would be optional

depending on my seniority. And I can see myself now

floating through walls and time-traveling to visit various

friends, lovers and historic figures and at times even

appearing again to the living. Giving some sound

advice to those I approve of and scaring the bejeebers

out of those who are obviously jerks. And so I’d win

the ghostly equivalent of medals and awards, maybe

even stipends and special privileges. And, because of

all that light coursing around at the end of the tunnel,

I’d see things I wasn’t able to, when alive. Whisper

to my literary critics, the real meanings of my metaphors.

And I’d do the Dance Macabre on Halloween nights

with super-attractive ghost princesses even though in life

I was clumsy as a log. Since gravity would have no effect,

we’d dance on the ceilings of haunted houses, tap dance

on the tables of mediums to the bright accompaniment

of clacking bones and a ghostly violin. And it will all be

great fun, for in Ghostland we won’t have to worry about

any of the constraints of earthly dimensions.

So now, still being alive, I think sometimes I might see

through the veil into an interesting future, with ditsy scholars

pouring over my papers and hard drives, and (with much

difficulty) trying to figure out which word goes where.

Finally asking, “Who wrote all of this abstruse and disjointed

stuff? Who was this language criminal anyway?”

This Tickle of Fear

At the top of the longest drop of the roller coaster,

walking the edge of a curb, imagining it to be the tiny

ledge of a sixty story building, bugs moving below,

looking up and shouting, “Oh my God, look up there,

will he fall, is he about to jump?” I know that fuzzy

feeling when fat fingertips embrace a two-edged razor

blade or when someone is about to sample my blood

with a not-too-sharp needle, or if one is compelled to

carry an almost full pot of boiling water across a room.

Then, there is this long descent down steep concrete

steps with no railing and in the dark. I feel it in my feet,

in my stomach. It bubbles up in me, and I am somewhere

between paralysis and that one rash step. I anticipate

the free fall, the hard crash of my skull against the sidewalk,

the opening flesh, my blood spattered everywhere, or

shall it be some scalding unendurable pain congealing

the skin, water like boiling acid, when I will have this

inclination to laugh, to laugh so hard my guts come tumbling

out of my mouth, and I soil my pants, go numb in the hands,

living so intensely and then suddenly . . . black out.

Reading & Writing Poetry

The more poetry I read, the freer I feel to be myself.

Even the bad poetry seems to work. I can see all

the possibilities then and it doesn’t matter if I’m

a screaming baby or a lethargic old man. It’s all

still there, a whole life which can be believed,

lived either backward or forward. Whether a lemon

drop or a moldering husk, the more I read, the more

I can see everything is both an ocean and a void:

the odor of long stored linen in a cedar chest in an

old house on an old street in the city, or the new

house in the burbs where outside a golden retriever

stands guard beside a split rail fence separating

your property from someone else’s cleared field.

In this autumn I discover poetry is not a thing but process,

not a long list of nouns but some very hair-raising verbs,

life upholding actions to be taken so that you’ll no

longer need to scratch open your wounds in anger nor

feel a pat on the back of the head by some reassuring

Angel. And you’ll no longer have to hide in a cage, be

someone else’s animal. There’ll be all these apposing

paths to take, where things both do and do not matter.

I’ve finally reached a point where reading a poem and

writing a poem are the same. It isn’t significant whose

name appends the poem. Subjects are the same. My faux

poem, “Falling Off an Elevator from the Ninetieth Floor

on Mid-Summer’s Eve,” is the same as Shakespeare‘s

Sonnet CLVI. Ask him, he’ll tell you.

“How?” you enquire, “Isn’t he supposed to be dead?”

Yes, I say, but he’ll talk anyway, he just loves to jabber.

Bury that dumb ballpoint of yours into paper and he’ll

Resurface . . . say some pretty profound and beautiful

things too. It’s all up to you (but it really isn’t, of course).

I’ve just read this Jack Gilbert guy so I really know.

And also Wallace Stevens, that old billy-goat of a man

with a buffalo head. They both knew all of the secrets:

the mysteries of the North and the South, the be all of,

of-all, and also what’s in between.

Absolving the Noisy Sleepers

after “Sleeping Beauty,” “Snow White,”

“The Brothers Grimm,” et al

Whoever they are, whatever their status, we are touched by

their stentorian lullabies, at once stunning and heavy

against walls, the floor tiles resonating, wild under our feet.

They, laying their heads on their own soft white beards that

curl around into spongy pillows, on guard in green stocking

caps which adds a touch of vegetable essence and finery

while they snooze in the brambled garden outside

the palace walls. They, with their heavy heads drooling

a kind of silvery spittle that attaches itself web like,

to the thorns: their dream, the fairytale dream of an

ingénue in some curvilinear ballet, with her exquisite

behind projected so naively while supine, her half smile

awaiting that oversized oafish hero who lugs himself in

to do the job with his blubbery lips, six shooter at

the ready, a kind of wand in a Freudian horse opera.

But aren’t we the kind of audience who somehow demands

something better after these years, after the ripening of her

jewel? So here we are, nodding in our seats, unable to enter

the dream but still we say to them, her protectors, “Be kind to

us as you have been to her, you with your casual nasal hairs

waving like seaweed in the spring tide, our ears oscillating in

phase with yours, so sympathetic to your off key caterwauling.

Unrepentant and guilty sleepers who may not be ready to fall

from humming grace into some sniveling mundane grayness.

Keep her safe inside sonorous blue cavities until the lumpy

Horseman’s leaden hoof sounds are finally lost, safe until some

right bright star turns to her and your roaring must fade at

last . . . when nothing more will be heard of this brilliant and

transparent epic but the silent white kiss of departing galaxies.”

Bypassing the Bricks and Mortar of Ordinary Existence: An Interview with Richard Pflum

By George Kalamaras

George Kalamaras: Thanks for agreeing to this interview, Dick. I’m really honored to have your work for a feature in The Wabash Watershed. Could you describe what you see as your primary themes and/or concerns in your poetry—not just in this feature, but in general?

Richard Pflum: I’d like to think I have no primary themes. For me poetry is the creation of memorable language, a block of language that seems pure gold, has magical properties, and creates pictures in my own and the reader’s mind. The sounds of the words themselves create a kind of web that is almost tactile. The feeling almost always comes after the words are down.

In my early years as a poet I saw the world in a more quotidian sense. Now that I’m old, the world has its meaning for me mostly as metaphor. Thus, in making poems I want to say things in a way that bypasses the bricks and mortar of ordinary existence. Yet since words have meanings I cannot completely ignore the sensory world. I really don’t know what I’m going to say until I say it. After I have written it down and can see it, the text may seem to reorganize itself. I may rewrite it in several different ways. I’m always looking for some kind of path through the text. I always want to create some kind of monument (to what and for whom, I’m not sure).

I find that my poems have a lot of anger and frustration which I try to soften with ambiguity and irony. I hate being yelled at or yelling at other people myself. Many of my poems turn out to be complaints although what I’d really like to write are many poems of praise and thanks, evocations of heaven on earth.

GK: You mentioned your early years as a poet. How did you start writing poetry? And who were some of the first poets you read? What was it about poetry that drew you into it?

RP: I started writing poetry seriously when I discovered I wasn’t a musician. I had tinkered around with it a bit even when I was in high school. I had a friend who wrote poetry who liked to try out his work by reciting it while we were walking home. He introduced me to the poets, E. A. Robinson and John Greenleaf Whittier, as well as to a little bit of Robert Frost and William Cullen Bryant. My friend who introduced me to the word “ecology” was very sympathetic to the New England transcendentalists, and so he read me some Emerson and Thoreau. Later I discovered poets like Edna St. Vincent Millay, e. e. cummings and T.S. Eliot. Later when I was in college I discovered W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas. At this time I was also reading a lot of fiction. I hadn’t found out I was a poet yet. While studying chemistry I only knew I missed music a lot.

When I knew for sure the music was gone there was a vacuum that had to be filled. I discovered a talent I didn’t know I had. Words came to me rather easily. I felt I had a taste for them, and since I had always liked to read, it was now perhaps a time to begin something serious with regard to writing. Poetry seemed to be the best choice: it was closer to music, I thought of it as being a purer more economical form of literature. Also, I liked it better. When it worked one could almost feel something click into place.

GK: I think that’s a powerful statement, in which you see poetry and music in similar terms. How and in what way is poetry like music for you?

RP: Music is my support. Some writers read other writers to stimulate the juices for creation. I listen to music. It’s not the impulse to create a song lyric that makes me sit down with a ballpoint and an opened tablet, but to create something equivalent to what I’ve been listening to, what makes me want to stand up, at least metaphorically. Music creates a kind of sensory web. One is held in a kind of balance on the air. The notes, the sounds, are like strands of a cobweb glistening in sunlight. Notes strung on a line are filaments. There is a tactility, a breathing, a pulse. Pictures are created, weather is created. We are convinced humanity is music. I let music create a weather inside my head. I expand into it. With music gone, words flow in to take the place of notes. I’m in another place and time. Sometimes I’m back in my childhood, the old summers, the language of my parents asking questions, my grandmother singing songs she knew as a child, When We Grow Too Old To Dream. My uncle playing the piano, my mother playing The March of the Wooden Soldiers, my favorite, on the big black piano. I hear music and know I have things to build. At night in bed I dream a Strauss Waltz but it is The Beautiful Blue Danube, and the waters are not blue but black. Where are my parents, I think? I am alone along a wet bank. Dark figures in the twilight dot the lawn. But I am away upstairs and hear the radio downstairs where my parents and grandparents have gathered. Tommy Dorsey is playing, I think. Dad mimics Bing Crosby, his favorite big band singer when we drive for cold, summer root beer in the humid car.

I started talking about poetry and music and got carried away by a long ago life, but both poetry and music will do that. And so music and poetry have so many qualities in common. Form is one, a frame in which a piece of music or a poem might sit in the form of a sonnet, villanelle, symphony, sonata, or song. Another might be tonality: sad or happy, major or minor. Size: long or short, fast or slow. Timbre: the distinguishing sounds of different instruments, different voices. The great difference between poetry and music is that musical notes have no intrinsic meaning while words do. In my own work I tend to give a great deal of importance to the sound of a poem. I want my poetry to have a distinguishing sound. I believe it is this quality that makes a poem memorable. Ideas are secondary in poetry. Not so in journalism or fiction. But in good fiction the author will be aware of tweaking some of the poetic elements in his or her writing to increase both its memorability and beauty. In any Art we want to elicit an emotional response.

GK: That’s a beautiful memory, Dick—and quite musically rendered, even. I think sound—in poetry, in music—is visceral. As such, it brings with it a great deal of knowledge that lies outside the boundaries of the intellect. Of course, that’s one area of understanding that poetry attempts to access. And I don’t think a poem can do that without its inherent musical quality, so I appreciate your lovely meditation on that.

I’d like to shift gears, slightly, and ask you about Indiana. You were born in Indiana, and you’ve spent most of your life here. Can you talk a little about how or in what way Indiana feeds your poetry—how it feeds your work either directly or indirectly? Is there anything that you think marks you as “an Indiana poet”?

RP: Since you raise the topic of being an Indiana writer, I’m not sure I can say that much about it since I have lived here all my life with no places to compare with except when I was in the Army for two years. I was stationed at Ft. Monmouth, New Jersey, for about seven months. I was quite near the sea and could walk to the U.S.O. beach in about twenty minutes. Also New York City was about an hour away by bus. I went there when I had money and no parades were scheduled at the base. I really did enjoy New York. I use to go to Greenwich Village to visit its strangeness and the literary landmarks. About Indiana I can say it’s an interesting place to say you’re from. Easterners ask about the 500 and farming and sometimes even about Indians and John Dillinger. I’ve met a few who knew something about I.U. basketball, or Notre Dame football.

There is something about living in Indiana that makes me feel that I am living outside the mainstream, that my interests are foreign to the world and the universe. I was a strange and spoiled kid with good and extremely patient parents. The first of four siblings, I became ill with rheumatic fever at the age of seven. I was in bed a whole year and waited on hand and foot like a little prince who developed a passion for comic books, which I had other people read to me. I learned to read for myself only when others stopped. When I was sound again I went back to school where I was an average student. I had heard words among teachers that I was an underachiever. At the time I didn’t quite know what that meant. I was quiet and polite and did show some areas of interest in science and music. In music, I loved to sing and competed in volume with other singers until my voice began to change. I was a year older than the other boys in the class because of my illness. I did not like to sing alto and so I began to lip sync and finally didn’t sing at all. At school I was quiet and polite. At home I often had screaming fits and had to be sent to my room until I had quieted myself. I was taking piano lessons then and began to read biographies of the great composers.

High School was another story where I wasn’t quite so lonely when I fell in with a few geeky people like myself. One was the editor of a school publication, another became a psychiatrist. The other was the high school poet I spoke of earlier. He finally became a botany professor at Wabash College.

GK: That’s a fascinating childhood you describe. That makes me think, there are likely some young poets who might read your poetry and interview here in The Wabash Watershed. What advice, if any, do you have for young poets?

RP: About any career in the Arts, I would tell any young person that the Art must choose you. It might take a while for that to happen. You may tinker in many mediums at first, but at sometime you will know. It will become your drug of choice. Then there is no turning back. You are competing with Shakespeare, Leonardo, Van Gogh, Beethoven. The stuff you deal with is magical and dangerous. Many times it seems to seek out those who are vulnerable and have felt some great loss. Art then is the consolation that replaces the irreplaceable.