I still remember hearing a serape-clad poet read his poems one fall evening in the late 1970s in the backroom of the Runcible Spoon coffeehouse in Bloomington. His poems seemed mercurial, electric, joyous, and spiritual. His cadences were vibrant and rich. I believe he even sang and chanted some lines, though—admittedly—I don’t know for sure where memory clarifies and where my transformations, these decades later, begin. However, I do remember leaving that reading deeply impressed with the immediacy of poetry and of that writer’s art. That poet was Thomas Hastings—poetic ambassador, verbal gunslinger, psychic trickster, and imagist guide. Tom Hastings was a poet I came to know and admire in the late 1970s—and with whom I finally reunited at the Fourth Street Festival of the Arts & Crafts in Bloomington this past Labor Day weekend. Even some thirty-five years later he remains open, ebullient, and even ecstatic in his embrace of the poem and its potential to shape one’s life and consciousness.

There is such lightness of being in a Tom Hastings poem, laced with serious purpose, what anthropologist Clifford Gertz might describe in other contexts as “deep play.” One senses a poetic consciousness that does not divide the psyche into overly neat binaries, a consciousness where the “work” of the poet is equally about learning to dance with the ups and downs of the world and with the processes of the poem. There’s a childlike innocence in Tom’s person and poems, something deeply infectious that encourages the reader to step into his spontaneous world in an attempt to uncover the deeper mysteries of what is, what has been, and what might be. While he exhibits some of the wonder of early Dadaists, Tom’s poems avoid any trace of nihilism that may accompany that vision. While his process shares affinities with the “spontaneous bop prosody” of the Beats, his poems appear more directed toward an enchantment of the inner workings of the human psyche.

Tom Hastings gets into and out of a poem in a calm whirlwind that harkens back to the compression of early Imagist poets but with the accompaniment of an ecstatic dance that transforms the image into a playful, primordial evocation. I love that about his work—how the poem, for him, is a joyous yet serious endorsement of visionary potential. I hope you enjoy the following feature of Tom’s poems, which includes a conversation about his intentions and poetic process. I am very grateful to have reunited with Tom and his daring work after thirty-five years, and I am honored to share his vision of wise-innocence with the readership of The Wabash Watershed.

—George Kalamaras

Biographical Note

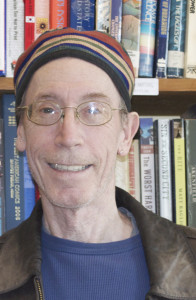

Thomas Hastings lives in Bloomington, Indiana. Recently retired, he taught language arts, Jungian psychology, and theatrical magic at Harmony High School for thirty-six years. He received a B.A. in Mythogenics from Antioch College in 1973 and has taken graduate classes at the California Institute of Asian Studies, The C. G. Jung Institute in Switzerland, and Indiana University. He’s been a Royal Scottish Arts Council Poet-in-the-Schools in Edinburgh and for the Indiana Arts Commission in Zionsville, Indiana. He created the Indianapolis Broadsheet, cofounded the Indianapolis Writers Center, and was poetry editor of its publication, InPrint. His poems have appeared in Aloe, Banyon Anthology #2, Celebrating Seventy, Indiannual II, The Linen Weave Anthology, The Windless Orchard, and others. He is the author of a dozen chapbooks, including Cynosure (Raintree Press, 1979) and Vertical Sleep, Horizontal Lies (Fly-by-Night, 1985). His volume of new and collected poems, Crop Circle Secrets, was published by Muse Rules Press in 2004. He fronted the poetry performance band, CoupCoupDaddy, for over a decade, and he is the foreign correspondent for Zoo & Logical Times. The most recent interview he gave appeared in 2012 in En Terex It—Encounters Around the Tarot (conducted by Enrique Enriquez). His spoken word is archived on WFIU’s The Poets Weave (programs: “Obsidian,” September 29, 2013 and “Later in France,” November 24, 2013).

Poems

Nine poems from a book in progress, Isso’s Adventures on the Magic Café Of Course love songs and poetry arm wrestle struggle to contest twilight you’re the blindfolded referee of course that was before they shot the stars out of your eyes along with the other curious desperados Vinegar Hill starting in front of his old home alfred kinsey rolls all the way down vinegar hill passes old peoples’ houses gains momentum speeding past student rentals car brakes screeching doesn’t slow for signs lucky that way herman wells at the bottom with his solemn stopwatch Yellow Jackets do not flail arms to ward off danger they do not like that freeze them midair with hairspray and the scent attracts more instead wear red be invisible Turtle Shaker in the old days men and women chanted at each other women would sing aphrodite’s pissed at you whatcha gonna do whatcha gonna do and the men would sing hey I lost my turtle shaker i bet you’re the one who found it give it back my turtle shaker Bitter Cold bitter cold and heavy nests in the north and midwest isso remembers one winter when crows dropped bones in the snow for sabrina the party dingo we keep them in the blue rose spinning altar that spring we had to cut down the spry woodpecker’s love drum tree and found binoculars inside Best Results we had best results with instant maple and brown sugar flavored cerrealism after we dismantled the microwave’s rotation device to eliminate unwanted mandalas in the oatmeal’s vision field morning after steaming morning midwinter ceremony animal masks surfaced on the heavy dark bowl’s shield Shine On shine on autumnal equinox old 3636 arrives on schedule from zargon where isso once filed stories on sacred cowmaidens escaped biobulls and twelve and a half minutes of missing crowd time when the six bells tolled and men on horses set the giant snowman on fire Last Time in Zargon last time isso was in zargon bus signs prohibited guitars and sombreros french folks increased social kisses you met acquaintances with when asked why he was there he replied he was on sabbatical and his country was too sad to make fun of so he had come to theirs to do so family and friends alike would chuckle and smile until they read what he wrote then no more cheek kisses Sometimes isso uses second sight sometimes to second guess perplexed spirits he’s not familiars with solara velossa lights a red candle a green baby cricket appears on the table why do we rehearse our dreams she asks chariots weigh more on carpets than on hardwood floors he carefully replies

Playing “Hide and Seek with Your Spirit and Soul”: An Interview with Thomas Hastings

By George Kalamaras

George Kalamaras: Tom, it’s great to have you in The Wabash Watershed. Thanks for agreeing to a little conversation as well. Let’s begin with your beginnings as a poet. How did you first come to poetry? What were your earliest influences (literary and otherwise)? What led you to becoming a poet?

Thomas Hastings: Great to be here, George! I’ve looked forward to visiting more with you as well, after many years. I’m looking forward to reading with you in December there in Fort Wayne along with so many other friends.

Jim Powell’s and my grandmother, Lenore Powell, spontaneously spouted a lot of poetry at us as when we were formulating our linguistic hemispheres—Tennyson, Wordsworth, Poe, James Whitcomb Riley. Her daughter, my mother Emma Louise, dropped out of IU to study for two years at Goodman Memorial Theater in Chicago to become a comedian. I gratefully use her make-up case as a close-up magic and oracular systems carrier.

I was a magician through childhood. Then, in early adolescence, my seventh grade chemistry teacher read my first poem aloud to the class. I was so delighted by their reactions that I started learning about and writing poems. As soon as I could drive, I performed poetry in Terre Haute coffeehouses. Through high school, I discovered the power and play of Dylan Thomas, the Beats, then W. S. Merwin.

Gregg Orr and Eric Horsting were valuable mentors in college, and Gregg introduced me to Robert Bly, whose work influences me more than any other. I’ve loved interacting with musicians and artists and their inspirational presences. And, of course, the Surrealists, Dadaists, and Jungian psychologists guided me from lead to gold and back again through the last half of the twentieth century.

GK: That’s quite a journey, and I love hearing about all the inroads—especially about the influence of elders. Too often in our culture, we neglect discussing the import of elder influence, and it can be profound, as it was with you and your grandmother. There’s also Bly in the mix for you here, too—another elder. In fact, I remember attending a Robert Bly reading in 1979 in Bloomington that you also attended. What is it about Bly’s work that influences you “more than any other”?

TH: As well as writing and translating, he’s devoted his life to helping lots of folks experience and understand better their own sacred and secular transitions—a primal function of poetry. I am drawn to his courageous, beautiful and surprising imagery as well as his fierce social and psychological erudition. I am particularly grateful for what I’ve learned from his musings about our oldest colors . . . black, white, and red . . . and their import in myths, fairytales, dreams, and poems.

GK: I hear you on Bly’s importance. For me, it was especially his bringing over of the work of Spanish and Latin American poetry into our readership—among many other gifts. To switch gears, and I hope not too abruptly, can you talk a little about your relationship—on a psychological and emotional level—to Indiana? Apparently, you grew up in Terre Haute? It seems you’ve spent the bulk of your life here in the middle of the country, although I know you spent an extended period in Switzerland (and perhaps elsewhere). What has Indiana given to your poetic vision? How, as a place, has it shaped your consciousness? What does it give you on a day-to-day level?

TH: I grew up in Noblesville, Elwood, and Brazil [Indiana], where I graduated from high school. My childhood is redolent with the Indiana Drain Tile Company, my grandfather’s factory in Brooklyn [Indiana]. He and my great grandfather leveled Mt. Aetna for its shale that they turned into clay and shaped and baked into tile pipes for chthonic use. I can still hear the KER-CHUNK of the two-story gas-driven shale planer as it sheared off another massive section of a once-tall hill. Primo easy-pickin’ fossil fields bloomed in its perimeter. I loved playing in the gigantic kilns, the abrupt echoes, the volcanic tang of coal burn undertoned with earthy baked clay. That is my alchemically salient regionality.

Of far greater impact are all the fine Indiana poets I’ve had the good fortune to meet and get to know over the decades. I’m thinking back of monthly Bloomington/Indianapolis writing workshops with Roger [Pfingston], Dick [Pflum], Bonnie [Maurer], Alice [Friman], Elizabeth [Krajeck], Eric [Rensberger], and Jennifer [Martin], and the careful consideration and support we gave to each other’s writing.

GK: Ah, the mysteries of childhood—the textures and smells and sounds! Community, too, is so important. I find it primary for poets—which is one reason for The Wabash Watershed—though it is tempting for some writers, at times, to think they operate alone, as the overly romanticized “artist.” So I really appreciate what you say about the monthly writing workshops in which you participated. What do you feel you gained poetically—and simply as a person—by being part of this community of poets?

TH: I accept the Jungian notion that consciousness comes from the unconscious and not the other way around. Gary Snyder encouraged me in the early 70s to value and seek fellow poets where I lived and grow community among them. Having a better understanding and grounding of where others’ poems come from has been essential to my own poetic as well as personal growth. Bly says children need to hear fairytales to reassure them they’re not crazy. That’s exactly what those folks and workshops did for me.

GK: I think that’s a beautiful way to see relationships. What about your relationships with books? Let’s expand this to a community of reading. It’s obvious to me in knowing you that you’re deeply affected by Jung. What are you reading these days—poetry or otherwise—with which you feel kinship and community?

TH: I just read Louise Erdrich’s Shadow Tag, and I’m eyeing Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 next and, thanks to our Half Price Book Store, I love delving into Lehman’s Best American Poetry series. I read prodigiously in the travel genre thanks to Paul Theroux. His novel, Milroy the Magician, is one I’ve recommended over and over to my high school students along with Geek Love (Dunne), A Prayer for Owen Meany (Irving), A Confederacy of Dunces (Toole), Solar Storm (Hogan), Middle Passage (Johnson), A Voyage to Arcturus (Lindsey), and Under the Skin (Faber).

GK: What would you say you try to accomplish in your poetry, Tom—emotionally, psychologically, culturally, and/or spiritually? In other words, what do you think you’re after in having taken up this practice for decades now?

TH: Facio, factus, fec, fic, fy! When I grin back at the unconscious, it takes a snapshot—a poem—with its transpersonal cell phone. The image could be simple or complex and ornately backgrounded. The poem’s intention seems to be to truthfully stitch together the inner world with the outer world equitably. “Rubbing the fire back into the ash.” And, it is the saying aloud of poems that releases their numinosity like the magic spells they are. My priority has always been the ecstatic oral tradition, George.

GK: I’ve certainly always felt that in your poems, even when I first heard you read in Bloomington, and I’ve valued that about you and your work. In fact, I just dug out my copy of your first book, Amulets (1974), in which you inscribed to me, in September of 1979, “Your brother discipline & your sister ecstasy.” Beautiful! Speaking of priorities in writing, poets have so many divergent intentions for their work. As a long-practicing poet, what advice about the practice of writing would you give to aspiring poets?

TH: Ah! 1979 inner beings! They’re sister discipline and brother ecstasy in the twenty-first century! I recommend writing poems as opportunities to play hide and seek with your spirit and soul and see who calls All-ee All-ee in Free first. Make writing poems an opportunity to explain the outer world to the 90 percent of us that isn’t human. Allez Allez Oop.

GK: Tom, could you talk a little bit about any current poetry projects you’re working on, as well as—possibly—any poetry projects you may be planning for the near future?

TH: According to the map, I’ll be finishing Isso’s Adventures on the Magic Café, the sequel to Crop Circle Secrets. And I have a new business card with an ouroborus symbol on it identifying me as an inner being worker.