It is my pleasure to welcome you to a special issue of The Wabash Watershed. Our July/August feature showcases the work of our prize winners in this year’s Indiana Poetry Awards. As Poet Laureate, I once again sponsored two poetry contests this year. While last year’s contest sought submissions for the two categories of “Rural” and “Urban,” this year’s focus was “Indiana History” and “Social Justice.” First prize winners in each category received an award of $100. Second and third place in each category received $50 each. The initial screening was done in committee by blind review. The nationally known poet, Patrick Lawler, of Le Moyne College, served as final judge.

The number and quality of poems submitted was further testament to the breadth and vigor of Indiana poetry. I want to offer special thanks to every contestant for taking the time to submit and for trusting The Wabash Watershed with their work. As Poet Laureate, I feel a special commitment not only to encouraging the proliferation of verse but also to rewarding the endeavors of Indiana poets and getting their poetry read as widely as possible. The results of the contest showcase the richness and diversity of our poets.

I offer congratulations to this year’s winners, whose fine work is featured in this issue! I am moved by the generosity of all those who submitted as well as the goodwill and expertise of this year’s judge, Patrick Lawler.

—George Kalamaras

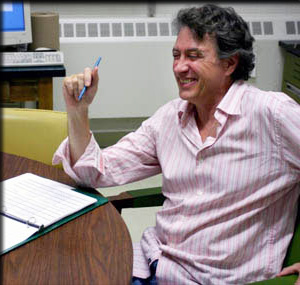

Final Judge

Patrick Lawler has published five collections of poetry, the most recent of which is Child Sings in the Womb (The Bitter Oleander Press, 2016). He has published a novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds (Fiction Collective 2, 2012) and a collection of short stories, The Meaning of If (Four Way Books, 2014). In addition, he has published a hybrid text combining poetry, memoir, and interview, Underground (Notes Toward an Autobiography) (Many Mountains Moving Press, 2011). Lawler has received numerous awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship, and he teaches at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York.

Indiana History

First Place: “A Brief History of the Mirror”

First Place: “A Brief History of the Mirror”

Patrick Kindig lives in Bloomington (Monroe County), where he’s currently working on a dual MFA/PhD at Indiana University. His micro-chapbook, Dry Spell, is forthcoming from Porkbelly Press in early 2016, and his work has appeared or is forthcoming in BLOOM, Court Green, Fugue, The Minnesota Review, and elsewhere.

A Brief History of the Mirror In the beginning there was mercury and a desire to see things backwards. Then there was mercury- poisoning and a mad polishing of glass and an ache for the days of reflecting pools, black ice, the accident of obsidian belched from volcanoes. This was the age of legends: Narcissus and Corinthians, Alice and Dorian Gray—all stories about love, of course. It was also the age of scientific discovery, when we learned that magnets have two poles. Then there was the great migration to basement apartments and economy lofts. Then there was dried toothpaste and mold smeared on every tiled wall. This is when water became a nuisance, when we began slamming warped doors against warped frames. Then there was a girl at the sink chasing shots of Crystal Palace with saltwater, fixing her hair on a Saturday night, the mirror white and opaque. Then the bathroom was empty. Then there was night, its interminable distances, the way it stretched out like a lake of molten silver. Then there was nothing but a handful of sea glass.

Second Place: “That Summer, a History”

Bonnie Maurer hales from Indianapolis (Marion County). Her poetry chapbooks include Reconfigured (Finishing Line Press, 2009), Bloodletting: A Ritual Poem for Women’s Voices (Ink Press, 1983), Old 37: The Mason Cows (Barnwood Press, 1981), and Ms. Lily Jane Babbitt Before the Ten O’clock Bus from Memphis Ran Over Her (Ink Press and Raintree Press, 1979).

That Summer, a History

That summer I wore tea rose,

the cheap perfume. My daughter

pressed her arms to my wrists,

we floated in that wind to the yard

to the garden swing—one yellow rose.

That summer before, I lost the milk song,

the baby wrapped in gypsy cloth, scarf

my grandmother sang of another summer

before the war, black river and

magenta roses knotted on her chest.

The baby tugged at my breasts and drank

each blossom free as I thought of ladders and

twisted the gypsy cloth fringe under

and over my fingers like the prayer

shawl strings I used to wind

around my hand as a child

until I could climb

its silk string ladder,

a traveler.

That summer I lost the cornucopia of my lover’s hands.

The space shuttle launched, progress sparked

the skies—magenta blooms. The horizon

divided our desires.

That summer my cousin the astronaut

became the name on a silver bridge

and I lost the lover

who pulled me from the dreamwater,

who loved to speak of the dollar

lost at nine from the Sisters of Precious Blood,

his early lessons learned in their silver roulette

wheel spinning, and in the relentless

keel of his father’s heart.

That summer before, my brother wanted

to leap like the fish, like the long, lake pike

my father pulled to the boat all those

dawn-light summers.

And how my brother looked upon

his father’s heart the way every morning

my son and I would look with wonder to see

if the heron stood in the river shallows.

That summer I lost one imagination.

The dinosaur my son pulled by his father’s belt

across the bedroom floor to Chicago

to see the sky scrapers. He pulled us all

across the sea-foam carpet—old bones—

we would get there.

But not my sister.

Wherever we went

strolling together,

combing our hair,

I promised my sister

god’s kiss in the cup,

goldfinch on the honey locust, taste of

lavender in the iris,

and into the weathered barn, the black

boots and silver spurs luring me,

I lost her by my father’s kiss.

That summer at the lake,

where the blue bird returned her weave,

lily pads, god’s burnished hearts,

lead like footprints from the water’s edge,

and I made myself into a pocket

for grief, shawl for comfort,

cloth for the table—

the place we begin again:

ripe strawberries in a blue dish,

loaf of bread and serrated knife.

Third Place: “Studebaker Wives”

Nancy Botkin lives in South Bend (St. Joseph County) and has been teaching first-year writing and creative writing at IU South Bend for 25 years. Her book, Parts That Were Once Whole, was published by Mayapple Press in 2007. She has also published the chapbooks Bent Elbow and Distance (Finishing Line Press, 2011) and In Waves (March Street Press, 2009).

Studebaker Wives 1. Outside, the low hanging branches serve up snow. Upstairs, in the room where her children ate and fought and had fevers, she packs the last box. She stacks the newspapers and listens to the train click-clack along tracks secured like the teeth of a zipper. 2. They think they are in heaven: payday, fat wallet, ice cream at Bonnie Doon. The neon lights throw bright shadows. They are dangerously close to a spark. She looks down at the impression he’s made, the angel he left in the snow. He feeds her hope as if through an IV. Soon, she’ll send their boy to the corner bar to find him. He’ll skip along, reminding her. 3. She watches the ghosts enter and exit through holes in the high windows of the corridor. She recalls the exact moment that her life began: white gloves white pearls baby’s breath. The end was more of a progression, more like the TV signing off: sweeping second hand high-pitched sound snow

Honorable Mention:

“Saint Theodora Guerin of Indiana”

Vienna Wagner, South Bend

Social Justice

Michael Derrick Hudson was born in Wabash, Indiana (Wabash County). He graduated from Indiana University and currently lives in Fort Wayne (Allen County). His poems have appeared in Boulevard, Georgia Review, Gulf Coast, New Ohio Review, Poetry, River Styx, and other journals. He was co-winner of the 2014 Manchester Poetry Prize.

Slave Cemetery

It was all over the news: parking garage construction

halted for a red plastic bucketful

of yellow crumbling bones. Some guy in a hardhat

complains movingly about lost wages while

an archaeologist in rubber boots probes the soil

against a background of cranes, ditches

and half-finished footers. The U.S. flag flutters fitfully

from the back of a cement mixer. So we finally know

what we built this city on. The mayor’s brow furrows

on television. Tough decisions

must be made, he says in a serious voice,

counting up the votes and not saying anything at all . . .

Here! Here! Here! is what the bones keep saying.

Nancy Botkin lives in South Bend (St. Joseph County) and has been teaching first-year writing and creative writing at IU South Bend for 25 years. Her book, Parts That Were Once Whole, was published by Mayapple Press in 2007. She has also published the chapbooks Bent Elbow and Distance (Finishing Line Press, 2011) and In Waves (March Street Press, 2009).

Missing A little moonlight through the trees, maybe. Scattered tufts of grass in an open field. What pecks, bores, or burrows raised its head to footsteps, to a rustling. the Real body found missing her body remote area Real disappearance inside pushed Real down Real dead Real body rode cause Real declined bed Real changed When the hard earth began to soften, there was endless talk about the weather. The skin of white over the field meant no harm.

Tracy Mishkin, PhD, is a call center veteran and an MFA student in Creative Writing at Butler University. Her chapbook, I Almost Didn’t Make It to McDonald’s, was published by Finishing Line Press in 2014. Her work has appeared in Little Patuxent Review, Postcard Poems and Prose, and Rat’s Ass Review. She is a native of Marion County and lives in Indianapolis.

Vision Problem Retinal floater jumping around my eye, looks like a jellyfish. Doctor says come back if it’s worse. Come back if you see flashes. If you wake up blurry, come back. If you don’t see color, come back. If you only see color. If it was his fault because he didn’t bring a gun to church. Her fault because whites were outnumbered at the pool. Because he looked like he had a gun. Because he was playing with a toy gun. Because she was sleeping in the wrong house. In the wrong neighborhood. Because six foot three two hundred pounds. Because mentally ill. Because asthma. Because accent. Because walking in the middle of the street. On the sidewalk. Because he ran. He looked them in the eye. She protested. Because black lives are insignificant if and only if nobody counts how many folks the cops have shot.

Honorable Mention:

“Illegal”

Jodie English, Indianapolis