The poems of JL Kato are poems of place. However, he doesn’t explore place in the traditional sense—in which one might describe and explore the immediacy of a particular region. Instead, his region is the soil of family, memory, and imagination—all of which work together to create networks of tree roots, grounding him in the present moment. As he says at the beginning of his poem, “Ghost Songs,” “I am giving life to ghosts.” And, indeed, he gives such life in many of his poems, as in the very moving “Miyoko’s Ashes,” where the speaker explores the recesses of loss at the death of his mother and deals with the question of what to do with her cremains: “What remains of relationships, / once fiery but now cold.” JL’s work also moves beyond family, extending into the places of cultural memory, as in, for example, his poem about the musician Glen Campbell. Wichita, Phoenix, and Albuquerque, locations from two of Campbell’s iconic songs, feel familiar to the reader and allow the poet to lament the isolating loss of the singer’s dementia and, by implication through such familiarity, other isolations the reader may experience in his or her own life. For JL, “place” even moves beyond personal and cultural/communal aspects to include the interstices of cosmological imagination, as in “Last Shiver,” in which he extends his reach across time, continent, and differing languages into poetic fellowship with the Nobel Laureate from Chile, Pablo Neruda: “Neruda’s moon lands gently on my bed.” JL’s reach into the regions with which one does not normally associate as “place” gives his poems a shimmering cord connecting a “then” to a “now,” granting him firm footing on the fertile ground of the present place of his psyche—the region, for him, where all things meet.

One of the great gifts of serving as Indiana’s poet laureate is the opportunity to become acquainted with poets who, in the midst of my often too-full schedule, might otherwise fall off my map. Thus, it was with great delight and awe that I first was introduced to JL’s poetry, hearing him read his work in Muncie nearly two years ago. He not only read moving poems, but he read them with power and commitment. There’s a passion in the way he explores his recesses of memory, a commitment to bringing over the past so that it might inform and shape the ever-present in generative ways.

I hope you enjoy the following feature of JL Kato’s poems, which includes a conversation about his processes and practice as a poet. I am grateful to be able to publish and share his work with the readership of The Wabash Watershed.

—George Kalamaras

Biographical Note

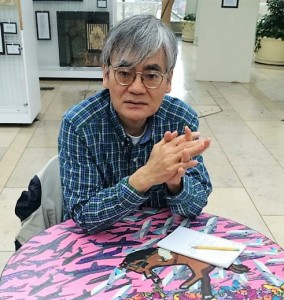

JL Kato was born in Japan but raised in Indiana since age two. His first collection of poems, Shadows Set in Concrete (Restoration Press, 2011) chronicles his experience as an immigrant. It won the poetry category, through the Indiana Center for the Book, in 2011 in the Best Books of Indiana competition. Kato graduated from Indiana University with a degree in journalism and worked as a newspaper copy editor for 31 years. His poems have been published in such publications as Arts & Letters, Contemporary American Voices, Paterson Literary Review, Raintown Review, and Tipton Poetry Journal, as well as in several anthologies. In 2009, he taught poetry to schoolchildren in Quezaltepeque, El Salvador. He is the poetry editor of The Flying Island, an online journal through the Indiana Writers Center. He also serves as president of Brick Street Poetry Inc., which brings poetry to public spaces. Kato and his wife, Mary Hawn, co-founded Poetry in Free Motion, a biennial collaboration between poets and quilters. He lives in Beech Grove.

Poems

Miyoko’s Ashes

What remains of relationships,

once fiery but now cold:

I hear my siblings squabbling

over my mother’s cremains.

They can’t decide where

or when to scatter them

and who should be in charge.

So they divide her up.

My sister wants to take the ashes

to Disney World, then to a beach

near Jupiter, as an offering

to Atlantic tides. I think Mom

would enjoy the Magic Kingdom.

Her nickname, after all, was Mickey.

One brother yearns to drop them

near the Golden Gate Bridge,

where Mom gasped while entering America.

I want to tell him to release a blossom

when he pours the ashes so he

can see which way they flow.

Another brother knows he will never

touch the sea. He wants to harbor ashes

in an urn on a mantelpiece, next

to a knick-knack, a hand-me-down

keepsake from Kyoto. I think

the warmth would comfort Mom.

This bickering is news, sad news,

to me, the son who shuns

all clamorous ceremonies.

I have no ashes to release.

Instead, I keep my mother

breathing in poems and memories.

I would tell my siblings, if I could,

in passing, that their mother

once said the ocean feels cold

but that she can find heat

in the arms of drowned seamen,

the embraces of muscular men.

Ghost Songs

I am giving life to ghosts.

Ironing table. Dimly lit corner.

My mother sings her favorite song:

I was dancing with my darling . . .

She hums until the end:

The beautiful Tennessee waltz.

Steam iron glides across my father’s shirt.

Another time: My best friend, Paul,

asks me to join him in “The Old Rugged Cross.”

He waves a Bible above his head. But no dice,

I’m not buying. The standoff lasts more

than 40 years. I love him anyway,

and he blesses me before he leaves.

Trembling hand. Tattered pages. Psalm 23.

The next ghost is me, teaching

my four-year-old daughter to sing

the song about a boy and his dragon, Puff.

Imagination ignites before she runs away

with the boy. Innocence doused.

One day, she will forget or not

be around, my ghost snuffed out.

Last Shiver

Neruda’s moon lands gently on my bed.

Light shimmers across my sheet.

A dream flickers:

Hollow trees filled with voices.

Phrases hanging like leaves:

snow garden, frozen pond

cracked stone.

Words swirling to the ground:

icicles,

arctic wind,

withered mum.

Which will cling to my cold-struck tongue?

“Sukiyaki” Reclaimed

The Japanese song “Ue o Muite Arukō” by Kyu Sakimoto was No. 1 in 1963.

The American release was titled “Sukiyaki,” which has nothing to do with

the original lyrics.

I look up so tears won’t fall,

remember a rain in spring.

My lonely walk tonight.

Through my tears, I count the stars,

remember a summer moon.

My lonely walk tonight.

Happiness soars above the clouds.

Sadness in the shadow of an owl.

In my lonely walk tonight,

I recall the autumn winds.

Eyes downcast so tears may fall.

Winter for Glen Campbell

The Wichita lineman’s

mind has gone haywire

and cold. Cables crisscross,

entangled on splintered

poles. His E string breaks.

Numb fingers drift

across the strings

between Phoenix

and Albuquerque,

but no, wrong song.

He’s in Kansas, where

that stretched-out A

can’t stand the strain

of dripping ice.

His stricken tongue

weighted with snow.

To a Quetzal

Modern conquistadores

plucked your plumes,

stripped your leafy habitat.

Yet before you fled

to the mountains,

your feathers dropped

on tin roofs

and tinted

the cinderblock walls

of Quezaltepeque.

The teals, purples and pinks

dance among blue flies

and yellow dogs.

Perhaps, one day

you will return,

when the morning sun

ignites the market street,

and the city will rise

from ashes,

the dust of plaster,

the husks of corn.

Embracing the “Bone Pile”: An Interview with JL Kato

By George Kalamaras

George Kalamaras: JL, it’s wonderful to have your work for The Wabash Watershed. I know you were born in Japan and adopted by an American serviceman and his Japanese bride. How old were you when you came to the United States, and did you come immediately to Indiana? Was leaving Japan a challenging cultural transition?

JL Kato: I was nearly two years old when I entered the United States. My adoptive father and his Japanese bride adopted me in Fukuoka, my birthplace. He was wounded during the Korean War and stationed in Japan afterward. He brought his new family to the United States in 1956, crossing the country before settling in northern Indiana and before moving to Indianapolis. My mother insisted I assimilate into American culture, so I was not exposed to the Japanese culture. Think about this. At age two, I was just getting the hang of speaking Japanese, then had to switch to a different language. I wasn’t able to converse with people until I was four or five. Then I couldn’t shut up. I became very verbal, amazing family and friends with my vocabulary and reading skills. I read Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur in third grade (the unabridged version). But other than the rice and fish my mother cooked, I knew little about Japanese culture. In my poetry, the stories I relate are based on tales my mother told me.

Kalamaras: That’s an intense and beautiful account. You mention the stories (given to you by your mother) about Japanese culture that you include in your poetry. What a lovely legacy. Is there a focus to those stories? That is, are they mostly family stories, say, or are they myths or folktales? How do you use the stories in your poems, and—I’m very curious—what have you learned most from having these stories in your life?

Kato: My mother told mostly family tales, such as the time my grandfather saved me from being washed away in a tsunami, or when she was a girl and was allowed to leave school to buy ice cream from a peddler. Though she adopted Lutheranism in America, she insisted on embracing her Shinto beliefs. I suspect, however, that my mother created myths about her life. For example, she claims that while attending an aunt’s funeral, the aunt’s soul possessed my mother’s body for several days. That was her reason for never attending a funeral in America. She also described one of her brothers, his body covered in tattoos and with several fingers missing. He supposedly was a member of the Yakuza (or commonly called the Japanese Mafia). As a teenager, I heard these stories and thought nothing of them. I was more concerned by the discrimination she encountered every day. At the time, she was a twice-divorced mother of five. When I began to write poetry as an empty-nest father, I realized these stories enabled my mother to step out of her nurturing role into one of a woman with dreams, fears, and hopes. I began to see the relationship between her struggles in America and the childhood stories of Japan. I began to reflect on the legacy I would leave my four daughters. That’s when my Japanese heritage poems, inspired by my mother’s stories, began to shape themselves. By reclaiming my Japanese identity, I hoped to pass that lore to my daughters. They had considered being part-Japanese exotic, yet they never had to suffer for that identity. I wanted to give them a glimpse of how brave their grandmother had been to endure growing up in an occupied country, then traveling to America on blind faith not knowing whether she would be welcomed or taunted.

Kalamaras: I’d like to shift the focus, now, from this most fascinating family and cultural influence to poetic influence. Who are the poets who have influenced you the most, and what, specifically, do you admire most about their writing?

Kato: Well, George, I am a latecomer to writing poetry. I didn’t start writing seriously until 1999. I never studied poetry formally. I had only occasionally read a poetry book. That said, I would say my early influences (pre-poetry) were two institutions: the singer-songwriter era of the ‘60s and ‘70s, plus my career as a newspaper copy editor.

I have always admired songs by Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Lennon and McCartney, John Prine, Laura Nyro, etc. Because most popular songs rely on only four chords, I turned to lyrics to hold my interest. I was amazed by inventive language, the economy of words wringing out the maximum of emotions. The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” showed me symbolism (“picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been,” “wearing the face that she keeps in a jar by the door”). Don McLean’s “Vincent” taught me the power of changing one line of a refrain (“perhaps they’ll listen now” vs. “perhaps they never will”). John Prine’s “Donald and Lydia” is a song that persuaded me it is okay to use irony, with its romantic imagining of two losers having a love affair. Neil Young’s “Ohio,” recorded days after the Kent State shootings, revealed the effectiveness of topical rage, of speaking truth to power. All of these lyrical lessons, plus hundreds of others, accumulated in my teenage brain and spilled out when I finally began to write poetry in my mid-forties.

As a copy editor, I learned how to edit tightly, a necessary skill when you have 24 inches of copy that has to squeeze into 15 inches on a news page. In headline writing, I strived to summarize complicated stories into a cramped space. If I was lucky, I could insert some wit or zing into the headline. These talents came in handy when I began to write poetry.

As for influential poets, there are two. Before I wrote poems, William Carlos Williams’ images, in tightly crafted little gems, bedazzled me. To me, they are haiku unchained by the aura of awe—simple language that evokes an immediate emotional response, something I aimed for in my headline writing. My earliest drafts imitated WCW.

After I began to write, I became enamored with Etheridge Knight’s poetry. Though I never met the man, who died in Indianapolis eight years before I began to write, I encountered his spirit in Indianapolis, where he left a legacy of spoken word and free workshops. The poets he mentored had a circuit of open mics. The first time I read at one, the sheet I was reading shook in my hand, and my words were rushed and sometimes inaudible. It was among this supportive community that I eventually found my voice—for reading aloud my poems and for the tone of my writing.

Kalamaras: That’s a wide and interesting net you throw. And I think that too often in conversations like this we neglect to mention cultural influences, so I’m glad you noted those. Beyond poetic and musical influences, what inspires you to write? In other words, this is a question about your poetic process. How does a poem come to you? Or how do you seek one out?

Kato: I rarely seek out a poem; I let it come to me. I find when I have a preconceived notion of what a poem should be, it rarely turns out well. Inspiration for a poem might be something I hear on the radio, the last thing I remember from a dream, or an offhand comment from a passerby. From these encounters, a phrase or line will reveal itself to me. I write it down and place it in what I call a “bone pile.” Then I let it ferment in my mind for a while, sometimes up to several weeks, before I try to expand on it. I realize letting a poem age is a maddeningly slow process, but I do work on several poems at a time. Nevertheless, I consider two keeper poems a month an achievement for me.

Kalamaras: What is it about living in Indiana that shapes your poetry, directly or indirectly?

Kato: You mean other than being indoctrinated in third grade to the dialect of James Whitcomb Riley? It was my first introduction to poetry. I survived.

Or how about encountering Hoosier hospitality as a whitewash of racial intolerance? My first book, Shadows Set in Concrete, chronicles my life as an immigrant in Indiana.

Or how about noticing a disturbing number of war monuments and memorials, but few structures honoring peace? Sorry to be negative here, but it is what I have seen and written about.

On a more positive note, tenderloin sandwiches, alley basketball, corn on the cob, forest wildlife, persimmon pudding, vibrant public libraries, elephant ears, murals and other street art—these are a few of the things that have popped up in my writing. I’m always on the lookout for identifying miracles in the mundane life of Hoosiers.

Kalamaras: What are you working on now, JL? Do you have a book of poems, or a series of poems, in the works? If not, what are the recent trends, tendencies, and/or images that are emerging in your current poems in process?

Kato: My current project is a series of midrash poems loosely based on Genesis. Last spring, I was among a dozen or so artists who were selected for a Religion, Spirituality & the Arts seminar, headed by Rabbi Sandy Sasso. We studied the Cain and Abel story and how the tale was presented in paintings, music, and literature. At the same time, each artist created a work that commented on the myth. My contribution was a ten-minute cycle of poems that delves into the motives for Cain’s murder and calls God to task for his part in the violence.

I am currently trying to craft another book, but the problem, as I said earlier, is that I work slowly on my poems. There are not enough quality poems for a full collection. Most of my recent work has been responses to popular music, such as Glen Campbell’s Alzheimer’s disease or imagining the man today who yelled “Judas” at Bob Dylan.

My style of poetry is changing. I am relying less on narrative and learning to trust the reader to understand the poem. One of these poems, “Flickers from Japan,” uses a montage of images to create a mood. The seemingly random phrases actually tell a story. It’s a technique I learned by studying Terrance Hayes’ “Wind in a Box.”